Last month, the Wisconsin town of Hazelhurst postponed discussion of a proposed ordinance due to a typo. The meeting agenda had incorrectly listed “wake board” instead of the intended “wake boat.” Said town chairman Ted Cushing, “I’m not going to violate the Open Meetings Law.”

Last month, the Wisconsin town of Hazelhurst postponed discussion of a proposed ordinance due to a typo. The meeting agenda had incorrectly listed “wake board” instead of the intended “wake boat.” Said town chairman Ted Cushing, “I’m not going to violate the Open Meetings Law.”

It was the right call, one that affirms my belief that public officials in Wisconsin are, by and large, intent on complying with the state’s openness laws. But, sadly, this is not always the case.

Recent weeks have brought forth two of the most egregious violations of the public’s right to know that I have seen in more than three decades of tracking openness issues on the Wisconsin Freedom of Information Council.

The first happened in the village of St. Francis, south of Milwaukee, on June 2. Megan Lee, a reporter for television station TMJ4, and photographer Dan Selan tried to attend a meeting of the St. Francis school board. The district superintendent, Deb Kerr, confronted Lee, in an exchange that Selan captured on video (see https://tinyurl.com/4pwr58z7).

“You are not allowed to come to our meetings because you did not give us any notice or tell us why you were here,” declared Kerr, saying she had just spoken with the district’s lawyer. “Like you said, it’s an open board meeting, but you’re not filming.” When Lee pressed for an explanation, Kerr replied, “I’m going to ask you to leave now, and if you don’t leave, I’ve already told you, I will call the police.” Thankfully, this did not occur.

For the record, no one is required to give advance notice before attending a public meeting. And the state’s Open Meetings Law, at 19.90, expressly directs all public bodies to “make a reasonable effort to accommodate any person desiring to record, film or photograph the meeting,” so long as it is not disruptive.

Kerr, a one-time candidate for state school superintendent, did apologize, sort of, saying “I wish I had handled it differently.” TMJ4 has filed a verified complaint against the school district with Milwaukee County’s Corporation Counsel, the first step toward possible legal action.

The second transgression involves Steven H. Gibbs, a circuit court judge in Chippewa County. Gibbs recently issued an order that not only barred the media from recording witness testimony at pretrial evidentiary hearings but also instructed that they “may not directly quote the testimony of the witnesses, and may only summarize the content of the testimony,” or else face contempt proceedings.

“Wow, this is quite the court order,” said Robert Drechsel, a UW-Madison professor emeritus of journalism and mass communication and expert on media law and the First Amendment, when I asked for his thoughts. He cited a 1976 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart, which limited judges’ ability to impose constraints on media, requiring that they consider less restrictive alternatives and ponder whether the order would be effective.

That was not done here. And, in fact, requiring summation over quotation “would be more likely to introduce a risk of error and possible prejudice,” Drechsel said. “So no, I do not think the judge can prohibit the media from directly quoting what they hear during an open court proceeding. And I don’t think it’s a close call.”

Judge Gibbs, asked under what authority he was forbidding direct quotation, cited a Wisconsin Supreme Court Rule that allows judges to “control the conduct of proceedings” before them. Gibbs said he believes in the First Amendment and freedom of the press but “my concern is a fair jury pool in this matter not tainted by any media reports” about evidence that may or may not be introduced. He did not explain how threatening the media for trying to be as accurate as possible would achieve this end. (For links to Gibbs’ and Drechsel’s full responses, see this column online.)

The truth is that public officials, even if they’re well-intentioned, sometimes broadly overstep. Let’s just be grateful that this is the exception and not the rule. You can quote me on that.

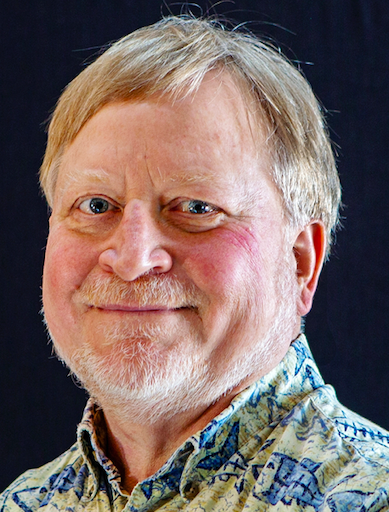

Your Right to Know is a monthly column distributed by the Wisconsin Freedom of Information Council (wisfoic.org), a group dedicated to open government. Bill Lueders is the group’s president.